Here’s to the next insurrection of the negroes in the West Indies,” Samuel Johnson once toasted at an Oxford dinner party, or so James Boswell claims. The veracity of Boswell’s biography—including its representation of Johnson’s position on slavery—has long been contested. In the course of more than a thousand pages, little mention is made of Johnson’s long-term servant, Francis Barber, who came into the writer’s house as a child after being taken to London from the Jamaican sugar plantation where he was born into slavery. Some of the surviving pages of Johnson’s notes for his famous dictionary have Barber’s handwriting on the back; there are scraps on which a twelve-year-old Barber practiced his own name while learning to write. Thirty years later, Johnson died and left Barber a sizable inheritance. But Boswell repeatedly minimizes Johnson’s abiding opposition to slavery—even that startling toast is characterized as an attempt to offend Johnson’s “grave” dinner companions rather than as genuine support for the enslaved. Boswell was in favor of slavery, and James Basker, a literary historian at Barnard College, has suggested that this stance tainted his depiction of Johnson’s abolitionism, especially since Boswell’s book appeared around the time that the British Parliament was voting on whether to end England’s participation in the international slave trade.

Johnson’s abolitionist views were likely influenced by Barber’s experience of enslavement. For much of the eighteenth century, Jamaica was the most profitable British colony and the largest importer of enslaved Africans, and Johnson once described it as “a place of great wealth and dreadful wickedness, a den of tyrants, and a dungeon of slaves.” He wasn’t the only Englishman paying close attention to rebellion in the Caribbean: abolitionists and slavers alike read the papers anxiously for news of slave revolts, taking stock of where the rebels came from, how adroitly they planned their attacks, how quickly revolts were suppressed, and how soon they broke out again.

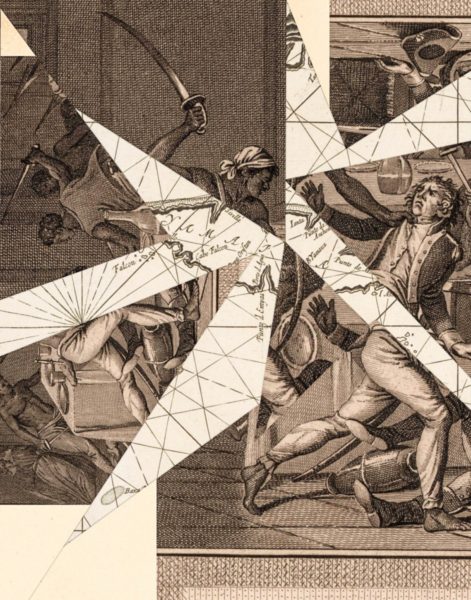

In a new book, the historian Vincent Brown argues that these rebellions did more to end the slave trade than any actions taken by white abolitionists like Johnson. “Tacky’s Revolt: The Story of an Atlantic Slave War” (Belknap) focusses on one of the largest slave uprisings of the eighteenth century, when a thousand enslaved men and women in Jamaica, led by a man named Tacky, rebelled, causing tens of thousands of pounds of property damage, leaving sixty whites dead, and leading to the deaths of five hundred of those who had participated or were accused of having done so. Brown’s most interesting claim is that Tacky and his comrades were not undertaking a discrete act of rebellion but, rather, fighting one of many battles in a long war between slavers and the enslaved. Both the philosopher John Locke and the self-emancipated Igbo writer Olaudah Equiano defined slavery as a state of war, but Brown goes further, describing the transatlantic slave trade as “a borderless slave war: war to enslave, war to expand slavery, and war against slaves, answered on the side of the enslaved by war against slaveholders, and also war among slaves themselves.”

Understood as a military struggle, slavery was a conflict staggering in its scale, even just in the Caribbean. Beginning in the seventeenth century, European traders prowled Africa’s Gold Coast looking to exchange guns, textiles, or even a bottle of brandy for able bodies; by the middle of the eighteenth century, slaves constituted ninety per cent of Europe’s trade with Africa. Of the more than ten million Africans who survived the journey across the Atlantic, six hundred thousand went to work in Jamaica, an island roughly the size of Connecticut. By contrast, four hundred thousand were sent to all of North America. (The domestic slave trade was another matter: by the time the Civil War began, there were roughly four million enslaved people living in the United States.)

Jamaica had hundreds of plantations, which grew cocoa, coffee, ginger, indigo, and, above all, sugar. Half the enslaved population labored on sugar plantations, where even a modest operation had a hundred and fifty slaves who worked year-round, planting, harvesting, and refining the crop, which was sold around the world. Brown’s previous book, “The Reaper’s Garden: Death and Power in the World of Atlantic Slavery,” described the miserable conditions that prevailed in Jamaica after the British seized control from the Spanish, in 1655. Mortality rates were exceptionally high for both Europeans and Africans, not only because of tropical diseases like malaria and yellow fever but also because of poor nutrition and oppressive working conditions. On some sugar plantations, there were twice as many deaths as births; the average slave could expect to survive only seven years of forced labor.

An Anglican missionary observed that the first toy given to white children in Jamaica was often a whip; the overseer Thomas Thistlewood, who managed forty-two slaves in St. Elizabeth Parish, kept a horrifying diary that describes how, in a single year, he whipped three-quarters of the men and raped half the women. When he moved to a different plantation, he threatened to dismember the enslaved men and women under his care, devising tortures and humiliations that included forcing some to defecate into other slaves’ mouths and urinate in others’ eyes, rubbing lime juice in their wounds after floggings, and covering a whipped, bound man in molasses while leaving him for the flies and mosquitoes. Alongside the daily temperature and rainfall, Thistlewood recorded the equally appalling behavior of his slaveowning neighbors. Those were scarce, however, since, by 1760, fewer than one in ten Jamaicans was white. There were so many Africans in Jamaica that the colonial government passed a law requiring plantation owners to have at least one white man for every twenty slaves on an estate. Most planters couldn’t comply, and the ratio was revised to one for every thirty.

The British had already learned how vulnerable white colonists were in Jamaica. Since their expulsion of the Spanish, they had been engaged in intermittent conflict with the Maroons, a population of former Spanish slaves who had fled into the Blue Mountains, in the island’s interior. Their name derived from the Spanish word for “wild,” and they had been imported from Africa to replace the indigenous people, the Arawaks, nearly all of whom had been killed by the Spanish. The Maroons had periodically raided British plantations, stolen supplies, and seized farmland. When the attacks escalated, in what became known as the First Maroon War, the island’s militia began retaliating, and it took more than ten years to reach a peace, in 1739. The British government agreed to recognize Maroon sovereignty in designated areas; the Maroons agreed to capture and return any runaway British slaves. There were other free blacks in Jamaica, too, including women who had been freed in the wills of white colonists who had kept them as concubines, and children who were the products of such unions.

The social hierarchies of the colony were complicated, and would only become more so. Just as many of the colonists who arrived in Jamaica were veterans of the British Army or the Royal Navy, many of the enslaved there had participated in armed conflicts before being forced into bondage. African states engaged in regional warfare long before European interference, and, after the transatlantic trade incentivized the kidnapping of enemies, the kingdoms of Akwamu, Akyem, Asante, Dahomey, Denkyira, and Oyo went to war with one another over territory, minerals, and people. Slaves from certain regions became more highly valued than others, including, for a time, the so-called Coromantee, who came from many different kingdoms on the Gold Coast.