What General Pershing Was Really Doing in the Philippines

August 24, 2017 · By JONATHAN M. KATZ for www.theatlantic.com

Trump has again recirculated a debunked history about terrorism. But what the general was really doing in the Philippines can tell us something more important about America.

U.S. General John Pershing with a group of officers at Zamboanga, Mindanao.

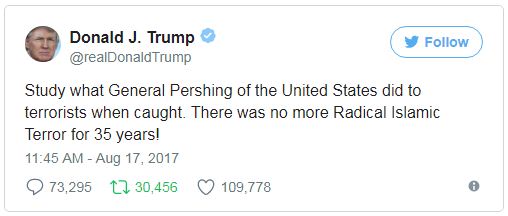

Another day, another sputtering orgy of confusion following a cryptic Donald Trump tweet. This one came Thursday, a few hours after a van plowed into a crowd on the Barcelona pedestrian mall of Las Ramblas, an attack claimed by the reeling Islamic State. The president replied, via iPhone:

It seemed to be a reference to a story Trump told at campaign rallies during the 2016 primaries, which in turn was a garbled version of an Islamophobic meme that has made its way around the internet for years. In the fable, the legendary U.S. General John J. Pershing once ended a wave of Muslim terrorism in the Philippines by executing prisoners with bullets dipped in pigs’ blood. Other superstitious fighters were so terrified by the prospect of being killed while touching part of a forbidden animal, the story goes, that fighting immediately stopped, for some period of time. (For 25 years, Trump said at a North Charleston, South Carolina, rally in February 2016; a few weeks later, in Costa Mesa, California, it had jumped up to 42.)

Journalists and commentators, who’ve gotten more comfortable calling out the president’s lies, turned to the fact-checks that circulated the last times he told the story, mainly on Snopes and Politifact. The general conclusions: that the story was bogus, implausible, and an insult to the memory of an American hero. In praising the execution of even fictitious prisoners, after all, Trump was endorsing a war crime. “I’ve never met an American officer who would carry out an order to commit an atrocity like this,” David French wrote in the National Review.

But that isn’t the whole story either. While Trump’s myth-peddling might not tell us much about fighting terror, looking harder at what Pershing was really doing in the Philippines, and how the hamburger history Trump keeps using to rally his supporters got made, can tell us something more important about America, and what we might expect from our government in the months and years to come.

Start with Trump’s definition of terrorism, a word which—it should be clear by now—the president uses, and pretty much only uses, to mean violence committed by Muslims. But that word doesn’t make much sense in Pershing’s context. In the first decades of the 20th century, Muslim Filipinos weren’t targeting American cities or kidnapping tourists. They were attacking American soldiers for one simple reason: The United States had invaded and was occupying their home.

In 1898, the United States annexed the Philippines, with a full-scale invasion and a $20 million payoff to the Spanish, who had colonized the islands for the previous 300 years. U.S. officials, including President William McKinley and his imperialist assistant secretary of the navy, Theodore Roosevelt, saw an opportunity to colonize the islands and take their land, resources and markets for trade—a new outpost of expansion at a moment when, for the first time since the arrival of European settlers, there was nothing left to conquer on North America. From 1899 to 1902, U.S. troops battled Filipino nationalists on the predominantly Catholic northern and central islands, until the provisional government was finally captured and surrendered.

As thousands of Americans and as many as 220,000 Filipinos died in that phase of the war, the U.S. had mostly avoided conflict in the southern, predominantly Muslim islands, including Mindanao and the Sulu Archipelago. Locals there, whom the Spanish had called “Moros” (the Spanish word for “Moor,” as in the Muslims of North Africa who had once controlled Spain) were as wary of the Catholic nationalists, who spoke different languages and had long had designs on their islands, as they were the white invaders.

An initial treaty between the U.S. and Muslim tribes was brokered by the sultan of the Ottoman Empire. But once the Americans defeated the northern revolutionaries, the Americans decided to take control over the southern islands, changed the agreement, and a new war broke out. The so-called Moro Rebellion ushered in a second wave of guerrilla and counterinsurgency campaigns, in which Americans used tactics they had picked up in the earlier wars: search-and-destroy missions, waterboarding captives, and forcing civilians into concentration camps—a word Americans learned for the first time during the period.

The Moros did not want to wage a holy war against the invaders, scholars Patricio Abinales and Donna Amoroso wrote in their book, State and Society in the Philippines. Rather, “they did not want to pay the invader’s tax or be subject to his laws, and they did not know or believe that the Americans would respect their religion. They wanted to keep their way of life. If they had been left alone they would have remained in grudging, perhaps sullen and suspicious, peace.”

U.S. military governors also established civil administration, building infrastructure and schools that taught entirely in English. But it took constant violence, and the constant threat of more, to keep the colonies in line. In a signal 1906 massacre of civilians and fighters at the volcano Bud Dajo, a veteran of the battle from Indiana later wrote, the Americans “turned that machine gun on them and they’d stand there, the Moros would, and just look like dominoes falling.”

Pershing took over the still-raging theater as military governor of what Americans were now calling the Moro Province in 1909. He instituted some reforms, including streamlining the legal system and helping expand trade in hemp, coconuts, and lumber, benefitting local traders as well as the U.S. businesses that were already growing rich off the occupation. But he continued believing that the threat of violence was necessary to keep control over a population that he, like most white Americans, had come to consider culturally and genetically inferior. “During the slow process of evolution leading up to civilization, the Moros must be kept in check by the actual application of force or by the moral effect of its presence,” Pershing wrote, in a letter later quoted by the historian Alfred W. McCoy.

The American general had developed these views in a career that began fighting, rounding up, and deporting American Indians from the land that became the western United States. He would continue putting them into practice after the Philippines, when he led the failed expedition into Mexico to capture the revolutionary Pancho Villa. They were typical of the deeply white supremacist Army that trained him. In their responses to Trump’s tweet, journalists happily relayed Pershing’s jaunty nickname, “Black Jack,” mostly without noting where it came from: When he was an instructor at West Point, all-white cadets blamed Pershing’s strict rules on his time as a commander of the 10th Cavalry Regiment, one of the African-American “Buffalo Soldiers” units, during the Indian Wars. (The original version of his nickname was “Nigger Jack.”)

In 1913, Pershing personally led American and Filipino troops in a fight against the last holdouts of Moro resistance in a cotta, or fort, on the mountain Bud Bagsak. By the end of the attack, the Muslim fighters had run out of bullets, and were left throwing their barong knives and daggers at the Americans. “One last assault, the walls were scaled, and the cotta fell. Almost every warrior, woman, and child in the cotta died,” Abinales and Amoroso have written. Hundreds of people were killed.

Though there is no evidence of anyone shooting anyone with bullets dipped in pig’s blood, according to Pershing’s memoirs, he did know about a tactic some American soldiers employed of occasionally burying Moro fighters with pig carcasses—a tactic the mostly Christian invaders thought might scare them into submission. But there is no evidence it worked. Instead, it was Pershing’s slaughter of civilians and fighters at Bud Bagsak that all but ended the Moro Rebellion, ensuring the southern islands would be incorporated into the Philippines and the first major territory in what would become America’s global empire.

Nor did it result in 42—or 35, or even 25—years of peace. The U.S. colonization of the Philippines continued until Dec. 8, 1941, when in a coordinated attack with their strike on the U.S. fleet in the similarly occupied territory of Hawaii (on the other side of the date line), the Japanese invaded, drove out the Americans and took over the Philippines for themselves. Five years later, after the Allies, including Filipino guerrillas, had defeated Japan in World War II, the U.S. finally granted the decimated islands their independence. Relations between the Christian and Muslim islands jammed together under Manila’s rule have been tense ever since.

America’s domination of the Philippines was controversial in the United States, with writers like Mark Twain and many politicians arguing for abuses to stop and the occupation—and others like it—to end. But it has been all but forgotten in the United States since then, only slipping back into the conversation at politically convenient moments, often as legend or myth. Snopes first rated the “pig’s blood” story as false back in 2001, when a version emerged as an email forward shortly after the Sept. 11 attacks. It was also shared at the time at a dinner party by Democratic Senator Bob Graham, then the chairman of the Senate Intelligence Committee. It appeared periodically since, before making its way to Trump. Even the National Review, which mocked the story yesterday, published its own version of the lie in 2002.

There are costs to not knowing this history. One is being fooled by seemingly easy answers to complex problems, like imagining one cool trick that could end the catastrophic wars ravaging Iraq, Syria, Afghanistan, and other Muslim nations—including the bloody, ongoing siege in Marawi, home to descendants of Moro fighters, now flying the Islamic State’s flag in one town of the southern Philippines. Another is being surprised and unprepared when faced with a leader such as Philippine President Rodrigo Duterte, who has been trying to use the bloody U.S. legacy to reposition his country closer to China at a precarious moment in Pacific relations. The forgetting also sows confusion and mistrust at home, when many in the black, Hispanic, and Asian-American communities, and other large swaths of the U.S. population, point out open wounds still affecting life in America today, only to be ignored or told to move on by people who at other turns claim to care deeply about preserving the legacy of the past.

There’s another possibility as well: that Trump and his advisors know more about the real history than they let on, and that they intend to repeat it.